Two Sample t-test

data: mathematicians and accountants

t = 0.46359, df = 21, p-value = 0.6477

alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

-6.569496 10.338727

sample estimates:

mean of x mean of y

53.50000 51.61538 Statistical Models

Lecture 4

Lecture 4:

Two-sample t-test &

More on R

Outline of Lecture 4

- Two-sample hypothesis tests

- Two-sample t-test

- Two-sample t-test: Example

- The Welch t-test

- The t-test for paired samples

- More on vectors

Part 1:

Two-sample

hypothesis tests

Overview

In Lecture 3:

- We looked at data on CCI before and after the 2008 crash

- In this case data for each month is directly comparable

- Can then construct the difference between the 2007 and 2009 values

- Analysis reduces from a two-sample to a one-sample problem

Question

Problem statement

Goal: compare mean and variance of 2 independent normal samples

- First sample:

- X_1, \ldots, X_n from normal population N(\mu_X,\sigma_X^2)

- Second sample:

- Y_1, \ldots, Y_m from normal population N(\mu_Y,\sigma_Y^2)

- We may have n \neq m

- Samples cannot be paired due to different size!

Tests available:

- Two-sample t-test to test for difference in means

- Two-sample F-test to test for difference in variances (next week)

Why is this important?

Hypothesis testing starts to get interesting with 2 or more samples

t-test and F-test show the normal distribution family in action

This is also the maths behind regression

- Same methods apply to seemingly unrelated problems

- Regression is a big subject in statistics

Normal distribution family in action

Two-sample t-test

- Want to compare the means of two independent samples

- At the same time population variances are unknown

- Therefore both variances are estimated with sample variances

- Test statistic is t_k-distributed with k linked to the total number of observations

Normal distribution family in action

Two-sample F-test

Want to compare the variance of two independent samples

This can be done by studying the ratio of the sample variances S^2_X/S^2_Y

We have already shown that \frac{(n - 1) S^2_X}{\sigma^2_X} \sim \chi^2_{n - 1} \qquad \frac{(m - 1) S^2_Y}{\sigma^2_Y} \sim \chi^2_{m - 1}

Normal distribution family in action

Two-sample F-test

Hence we can study statistic F = \frac{S^2_X / \sigma_X^2}{S^2_Y / \sigma_Y^2}

We will see that F has F-distribution (next week)

Part 2:

Two-sample t-test

The two-sample t-test

Assumptions: Suppose given samples from 2 independent normal populations

- X_1, \ldots ,X_n iid with distribution N(\mu_X,\sigma_X^2)

- Y_1, \ldots ,Y_m iid with distribution N(\mu_Y,\sigma_Y^2)

Further assumptions:

- In general n \neq m, so that one-sample t-test cannot be applied

- The two populations have same variance \sigma^2_X = \sigma^2_Y = \sigma^2

Note: Assuming same variance is simplification. Removing it leads to Welch t-test

The two-sample t-test

Goal: Compare means \mu_X and \mu_Y

Hypothesis set: We test for a difference in means H_0 \colon \mu_X = \mu_Y \qquad H_1 \colon \mu_X \neq \mu_Y

t-statistic: The general form is T = \frac{\text{Estimate}-\text{Hypothesised value}}{\text{e.s.e.}}

The two-sample t-statistic

Define the sample means \overline{X} = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n X_i \qquad \qquad \overline{Y} = \frac{1}{m} \sum_{i=1}^m Y_i

Notice that {\rm I\kern-.3em E}[ \overline{X} ] = \mu_X \qquad \qquad {\rm I\kern-.3em E}[ \overline{Y} ] = \mu_Y

Therefore we can estimate \mu_X - \mu_Y with the sample means, that is, \text{Estimate} = \overline{X} - \overline{Y}

The two-sample t-statistic

Since we are testing for difference in mean, we have \text{Hypothesised value} = \mu_X - \mu_Y

The Estimated Standard Error is the standard deviation of estimator \text{e.s.e.} = \text{Standard Deviation of } \overline{X} -\overline{Y}

The two-sample t-statistic

Therefore the two-sample t-statistic is T = \frac{\overline{X} - \overline{Y} - (\mu_X - \mu_Y)}{\text{e.s.e.}}

Under the Null Hypothesis that \mu_X = \mu_Y, the t-statistic becomes T = \frac{\overline{X} - \overline{Y} }{\text{e.s.e.}}

A note on the degrees of freedom (df)

The general rule is \text{df} = \text{Sample size} - \text{No. of estimated parameters}

Sample size in two-sample t-test:

- n in the first sample

- m in the second sample

- Hence total number of observations is n + m

No. of estimated parameters is 2: Namely \mu_X and \mu_Y

Hence degree of freedoms in two-sample t-test is {\rm df} = n + m - 2 (more on this later)

The estimated standard error

Recall: We are assuming populations have same variance \sigma^2_X = \sigma^2_Y = \sigma^2

We need to compute the estimated standard error \text{e.s.e.} = \text{Standard Deviation of } \ \overline{X} -\overline{Y}

Variance of sample mean was computed in the Lemma in Slide 72 Lecture 2

Since \overline{X} \sim N(\mu_X,\sigma^2) and \overline{Y} \sim N(\mu_Y,\sigma^2), by the Lemma we get {\rm Var}[\overline{X}] = \frac{\sigma^2}{n} \,, \qquad \quad {\rm Var}[\overline{Y}] = \frac{\sigma^2}{m}

The estimated standard error

Since X_i and Y_i are independent we get {\rm Cov}(X_i,Y_j)=0

By bilinearity of covariance we infer {\rm Cov}( \overline{X} , \overline{Y} ) = \frac{1}{n \cdot m} \sum_{i=1}^n \sum_{j=1}^m {\rm Cov}(X_i,Y_j) = 0

We can then compute \begin{align*} {\rm Var}[ \overline{X} - \overline{Y} ] & = {\rm Var}[ \overline{X} ] + {\rm Var}[ \overline{Y} ] - 2 {\rm Cov}( \overline{X} , \overline{Y} ) \\ & = {\rm Var}[ \overline{X} ] + {\rm Var}[ \overline{Y} ] \\ & = \sigma^2 \left( \frac{1}{n} + \frac{1}{m} \right) \end{align*}

The estimated standard error

Taking the square root gives \text{S.D.}(\overline{X} - \overline{Y} )= \sigma \ \sqrt{\frac{1}{n}+\frac{1}{m}}

Therefore, the t-statistic is T = \frac{\overline{X} - \overline{Y} - (\mu_X - \mu_Y)}{\text{e.s.e.}} = \frac{\overline{X} - \overline{Y} - (\mu_X - \mu_Y)}{\sigma \ \sqrt{\dfrac{1}{n}+\dfrac{1}{m}}}

Estimating the variance

The t-statistic is currently T = \frac{\overline{X} - \overline{Y} - (\mu_X - \mu_Y)}{\sigma \ \sqrt{\dfrac{1}{n}+\dfrac{1}{m}}}

Variance \sigma^2 is unknown: we need to estimate it!

Define the sample variances

S_X^2 = \frac{ \sum_{i=1}^n X_i^2 - n \overline{X}^2 }{n-1} \qquad \qquad S_Y^2 = \frac{ \sum_{i=1}^m Y_i^2 - m \overline{Y}^2 }{m-1}

Estimating the variance

Recall that X_1, \ldots , X_n \sim N(\mu_X, \sigma^2) \qquad \qquad Y_1, \ldots , Y_m \sim N(\mu_Y, \sigma^2)

From Lecture 2, we know that S_X^2 and S_Y^2 are unbiased estimators of \sigma^2, i.e. {\rm I\kern-.3em E}[ S_X^2 ] = {\rm I\kern-.3em E}[ S_Y^2 ] = \sigma^2

Therefore, both S_X^2 and S_Y^2 can be used to estimate \sigma^2

Estimating the variance

We can improve the estimate of \sigma^2 by combining S_X^2 and S_Y^2

We will consider a (convex) linear combination S^2 := \lambda_X S_X^2 + \lambda_Y S_Y^2 \,, \qquad \lambda_X + \lambda_Y = 1

S^2 is still an unbiased estimator of \sigma^2, since \begin{align*} {\rm I\kern-.3em E}[S^2] & = {\rm I\kern-.3em E}[ \lambda_X S_X^2 + \lambda_Y S_Y^2 ] \\ & = \lambda_X {\rm I\kern-.3em E}[S_X^2] + \lambda_Y {\rm I\kern-.3em E}[S_Y^2] \\ & = (\lambda_X + \lambda_Y) \sigma^2 \\ & = \sigma^2 \end{align*}

Estimating the variance

We choose coefficients \lambda_X and \lambda_Y which reflect sample sizes \lambda_X := \frac{n - 1}{n + m - 2} \qquad \qquad \lambda_Y := \frac{m - 1}{n + m - 2}

Notes:

We have \lambda_X + \lambda_Y = 1

Denominators in \lambda_X and \lambda_Y are degrees of freedom {\rm df } = n + m - 2

This choice is made so that S^2 has chi-squared distribution (more on this later)

Pooled estimator of variance

Definition

Note:

- n=m implies \lambda_X = \lambda_Y

- In this case S_X^2 and S_Y^2 have same weight in S_p^2

The two-sample t-statistic

The t-statistic has currently the form T = \frac{\overline{X} - \overline{Y} - (\mu_X - \mu_Y)}{\sigma \ \sqrt{\dfrac{1}{n}+\dfrac{1}{m}}}

We replace \sigma with the pooled estimator S_p

The two-sample t-statistic

Definition

Note: Under the Null Hypothesis that \mu_X = \mu_Y this becomes T = \frac{\overline{X} - \overline{Y}}{ S_p \ \sqrt{\dfrac{1}{n}+\dfrac{1}{m}}} = \frac{\overline{X} - \overline{Y}}{ \sqrt{ \dfrac{ (n-1) S_X^2 + (m-1) S_Y^2 }{n + m - 2} } \ \sqrt{\dfrac{1}{n}+\dfrac{1}{m}}}

Distribution of two-sample t-statistic

Theorem

Distribution of two-sample t-statistic

Proof

We have already seen that \overline{X} - \overline{Y} is normal with {\rm I\kern-.3em E}[\overline{X} - \overline{Y}] = \mu_X - \mu_Y \qquad \qquad {\rm Var}[\overline{X} - \overline{Y}] = \sigma^2 \left( \frac{1}{n} + \frac{1}{m} \right)

Therefore we can rescale \overline{X} - \overline{Y} to get U := \frac{\overline{X} - \overline{Y} - (\mu_X - \mu_Y)}{ \sigma \sqrt{ \dfrac{1}{n} + \dfrac{1}{m}}} \sim N(0,1)

Distribution of two-sample t-statistic

Proof

We are assuming X_1, \ldots, X_n iid N(\mu_X,\sigma^2)

Therefore, as already shown, we have \frac{ (n-1) S_X^2 }{ \sigma^2 } \sim \chi_{n-1}^2

Similarly, since Y_1, \ldots, Y_m iid N(\mu_Y,\sigma^2), we get \frac{ (m-1) S_Y^2 }{ \sigma^2 } \sim \chi_{m-1}^2

Distribution of two-sample t-statistic

Proof

Since X_i and Y_j are independent, we also have that \frac{ (n-1) S_X^2 }{ \sigma^2 } \quad \text{ and } \quad \frac{ (m-1) S_Y^2 }{ \sigma^2 } \quad \text{ are independent}

In particular we obtain \frac{ (n-1) S_X^2 }{ \sigma^2 } + \frac{ (m-1) S_Y^2 }{ \sigma^2 } \sim \chi_{n-1}^2 + \chi_{m-1}^2 \sim \chi_{m + n- 2}^2

Distribution of two-sample t-statistic

Proof

Recall the definition of S_p^2 S_p^2 = \frac{(n-1) S_X^2 + (m-1) S_Y^2}{ n + m - 2 }

Therefore V := \frac{ (n+m-2) S_p^2 }{ \sigma^2 } = \frac{ (n - 1) S_X^2}{ \sigma^2} + \frac{ (m-1) S_Y^2 }{ \sigma^2 } \sim \chi_{n + m - 2}^2

Distribution of two-sample t-statistic

Proof

- Rewrite T as \begin{align*} T & = \frac{\overline{X} - \overline{Y} - (\mu_X - \mu_Y)}{ S_p \ \sqrt{\dfrac{1}{n}+\dfrac{1}{m}}} \\ & = \frac{\overline{X} - \overline{Y} - (\mu_X - \mu_Y)}{ \sigma \sqrt{ \dfrac{1}{n} + \dfrac{1}{m} } } \Bigg/ \sqrt{ \frac{ (n + m - 2) S_p^2 \big/ \sigma^2}{ (n+ m - 2) } } \\ & = \frac{U}{\sqrt{V/(n+m-2)}} \end{align*}

Distribution of two-sample t-statistic

Proof

By construction \overline{X}- \overline{Y} is independent of S_X^2 and S_Y^2

Therefore \overline{X}- \overline{Y} is independent of S_p^2

We conclude that U and V are independent

In conclusion, we have shown that T = \frac{U}{\sqrt{V/(n+m-2)}} \,, \qquad U \sim N(0,1) \,, \qquad V \sim \chi_{n + m - 2}^2

By the Theorem in Slide 118 of Lecture 2, we conclude that T \sim t_{n+m-2}

The two-sample t-test

Suppose given two independent samples

- Sample x_1, \ldots, x_n from N(\mu_X,\sigma^2) of size n

- Sample y_1, \ldots, y_m from N(\mu_Y,\sigma^2) of size m

The two-sided hypothesis for difference in means is H_0 \colon \mu_X = \mu_Y \,, \quad \qquad H_1 \colon \mu_X \neq \mu_Y

The one-sided alternative hypotheses are H_1 \colon \mu_X < \mu_Y \quad \text{ or } \quad H_1 \colon \mu_X > \mu_Y

Procedure: 3 Steps

- Calculation: Compute the two-sample t-statistic t = \frac{ \overline{x} - \overline{y}}{ s_p \ \sqrt{ \dfrac{1}{n} + \dfrac{1}{m} }} where sample means and pooled variance estimator are \overline{x} = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n x_i \qquad \overline{y} = \frac{1}{m} \sum_{i=1}^m y_i \qquad s_p^2 = \frac{ (n-1) s_X^2 + (m - 1) s_Y^2 }{ m + n - 2} s_X^2 = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^n x_i^2 - n \overline{x}^2}{n-1} \qquad s_Y^2 = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^m y_i^2 - m \overline{y}^2}{m-1}

- Statistical Tables or R: Find either

- Critical value t^* in Table 1

- p-value in R

- Interpretation: Reject H_0 when either p < 0.05 \qquad \text{ or } \qquad t \in \,\,\text{Rejection Region} \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad (T \, \sim \, t_{n+m-1})

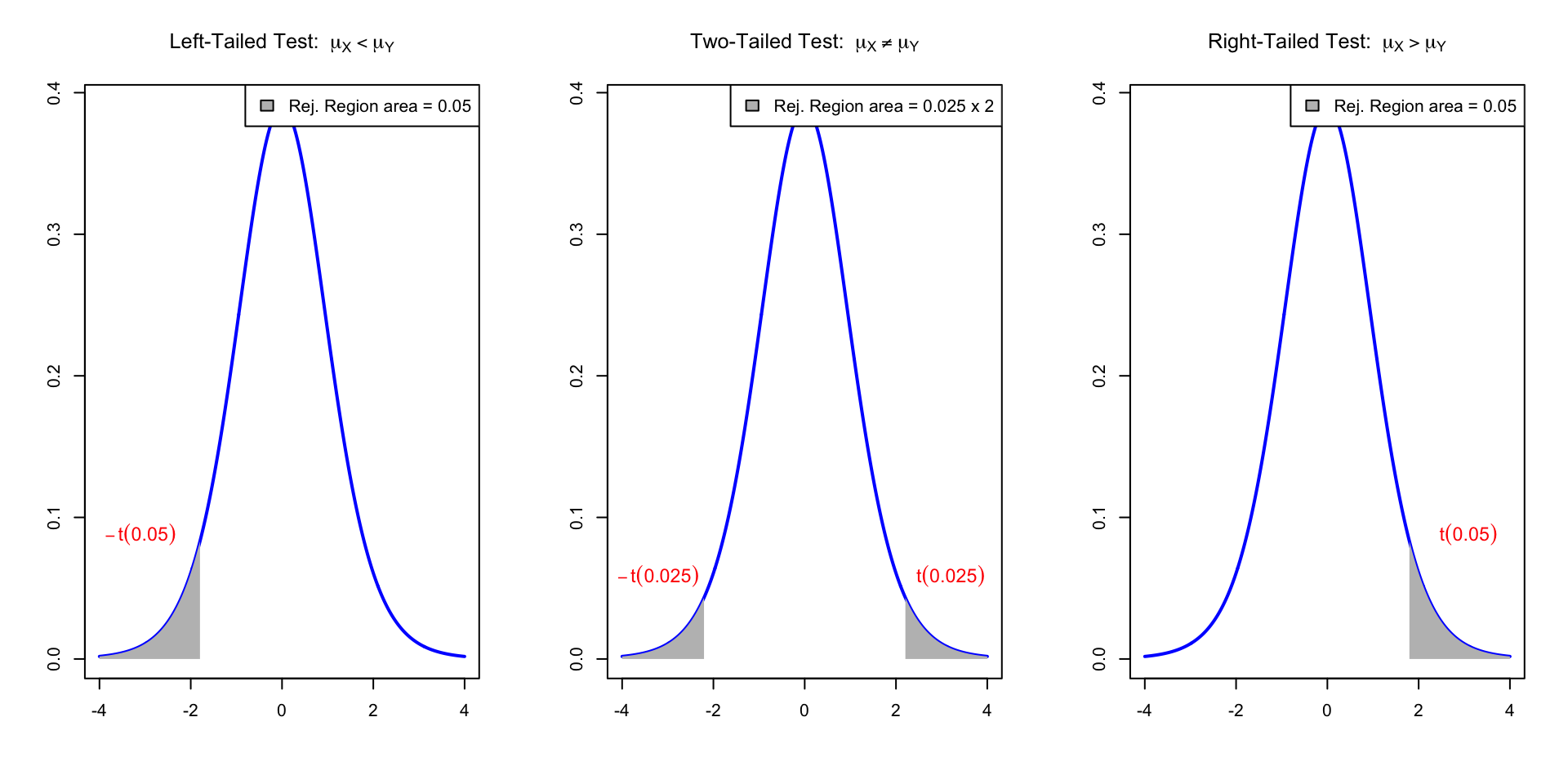

| Alternative | Rejection Region | t^* | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| \mu_X \neq \mu_Y | |t| > t^* | t_{n+m-1}(0.025) | 2P(T > |t|) |

| \mu_X < \mu_Y | t < - t^* | t_{n+m-1}(0.05) | P(T < t) |

| \mu_X > \mu_Y | t > t^* | t_{n+m-1}(0.05) | P(T > t) |

Reject H_0 if t-statistic t falls in the Rejection Region (in gray). Here t \sim t_{n+m-1}

The two-sample t-test in R

General commands

- Store the samples x_1,\ldots,x_n and y_1,\ldots,y_m in two R vectors

x <- c(x1, ..., xn)\qquady <- c(y1, ..., ym)

- Perform a two-sample t-test on

xandy

| Alternative | R command |

|---|---|

| \mu_X \neq \mu_Y | t.test(x, y, var.equal = T) |

| \mu_X < \mu_Y | t.test(x, y, var.equal = T, alt = "less") |

| \mu_X > \mu_Y | t.test(x, y, var.equal = T, alt = "greater") |

- Read output: similar to one-sample t-test

- The main quantity of interest is p-value

Comments on command t.test(x, y)

Warning: If var.equal = T is not specified then

R assumes that populations have different variance \sigma_X^2 \neq \sigma^2_Y

In this case the t-statistic t = \frac{ \overline{x} - \overline{y} }{s_p \sqrt{ \dfrac{1}{n} + \dfrac{1}{m} }} is NOT t-distributed

R performs the Welch t-test instead of the classic t-test

(more on this later)

Part 3:

Two-sample t-test

Example

| Mathematicians | x_1 | x_2 | x_3 | x_4 | x_5 | x_6 | x_7 | x_8 | x_9 | x_{10} |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wages | 36 | 40 | 46 | 54 | 57 | 58 | 59 | 60 | 62 | 63 |

| Accountants | y_1 | y_2 | y_3 | y_4 | y_5 | y_6 | y_7 | y_8 | y_9 | y_{10} | y_{11} | y_{12} | y_{13} |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wages | 37 | 37 | 42 | 44 | 46 | 48 | 54 | 56 | 59 | 60 | 60 | 64 | 64 |

Samples: Wage data on 10 Mathematicians and 13 Accountants

- Wages are independent and normally distributed

- Populations have equal variance

Quesion: Is there evidence of differences in average pay?

Answer: Two-sample two-sided t-test for the hypothesis H_0 \colon \mu_X = \mu_Y \,,\qquad H_1 \colon \mu_X \neq \mu_Y

Calculations: First sample

Sample size: \ n = No. of Mathematicians = 10

Mean: \bar{x} = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^n x_i}{n} = \frac{36+40+46+ \ldots +62+63}{10}=\frac{535}{10}=53.5

Variance: \begin{align*} s^2_X & = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^n x_i^2 - n \bar{x}^2}{n -1 } \\ \sum_{i=1}^n x_i^2 & = 36^2+40^2+46^2+ \ldots +62^2+63^2 = 29435 \\ s^2_X & = \frac{29435-10(53.5)^2}{9} = 90.2778 \end{align*}

Calculations: Second sample

Sample size: \ m = No. of Accountants = 13

Mean: \bar{y} = \frac{37+37+42+ \dots +64+64}{13} = \frac{671}{13} = 51.6154

Variance: \begin{align*} s^2_Y & = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^m y_i^2 - m \bar{y}^2}{m - 1} \\ \sum_{i=1}^m y_i^2 & = 37^2+37^2+42^2+ \ldots +64^2+64^2 = 35783 \\ s^2_Y & = \frac{35783-13(51.6154)^2}{12} = 95.7564 \end{align*}

Calculations: Pooled Variance

Pooled variance: \begin{align*} s_p^2 & = \frac{(n-1) s_X^2 + (m-1) s_Y^2}{ n + m - 2} \\ & = \frac{(9) 90.2778 + (12) 95.7564 }{ 10 + 13 - 2} \\ & = 93.40843 \end{align*}

Pooled standard deviation: s_p = \sqrt{93.40843} = 9.6648

Calculations: t-statistic

- Calculation: Compute the two-sample t-statistic

\begin{align*} t & = \frac{\bar{x} - \bar{y} }{s_p \ \sqrt{\dfrac{1}{n}+\dfrac{1}{m}}} \\ & = \frac{53.5 - 51.6154}{9.6648 \times \sqrt{\dfrac{1}{10}+\dfrac{1}{13}}} \\ & = \frac{1.8846}{9.6648{\times}0.4206} \\ & = 0.464 \,\, (3\ \text{d.p.}) \end{align*}

Completing the t-test

- Referencing Tables:

- Degrees of freedom are {\rm df} = n + m - 2 = 10 + 13 - 2 = 21

- Find corresponding critical value in Table 1 t_{21}(0.025) = 2.08 (Note the value 0.025, since this is two-sided test)

Completing the t-test

- Interpretation:

- We have that | t | = 0.464 < 2.08 = t_{21}(0.025)

- t falls in the acceptance region

- Therefore the p-value satisfies p>0.05

- There is no evidence (p>0.05) in favor of H_1

- Hence we accept that \mu_X = \mu_Y

- Conclusion: Average pay levels seem to be the same for both professions

The two-sample t-test in R

This is a two-sided t-test with assumption of equal variance. The p-value is

p = 2 P(t_{n-1} > |t|) \,, \qquad t = \frac{\bar{x} - \bar{y} }{s_p \ \sqrt{1/n + 1/m}}

# Enter Wages data in 2 vectors using function c()

mathematicians <- c(36, 40, 46, 54, 57, 58, 59, 60, 62, 63)

accountants <- c(37, 37, 42, 44, 46, 48, 54, 56, 59, 60, 60, 64, 64)

# Two-sample t-test with null hypothesis mu_X = mu_Y

# and equal variance assumption. Store result in answer and print.

answer <- t.test(mathematicians, accountants, var.equal = TRUE)

print(answer)- Code can be downloaded here two_sample_t_test.R

Comments on output:

- First line: R tells us that a Two-Sample t-test is performed

- Second line: Data for t-test is

mathematiciansandaccountants

Two Sample t-test

data: mathematicians and accountants

t = 0.46359, df = 21, p-value = 0.6477

alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

-6.569496 10.338727

sample estimates:

mean of x mean of y

53.50000 51.61538 Comments on output:

- Third line:

- The t-statistic computed is t = 0.46359

- Note: This coincides with the one computed by hand!

- There are 21 degrees of freedom

- The p-values is p = 0.6477

Two Sample t-test

data: mathematicians and accountants

t = 0.46359, df = 21, p-value = 0.6477

alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

-6.569496 10.338727

sample estimates:

mean of x mean of y

53.50000 51.61538 Comments on output:

- Fourth line: The alternative hypothesis is that the difference in means is not zero

- This translates to H_1 \colon \mu_X \neq \mu_Y

- Warning: This is not saying to reject H_0 – R is just stating H_1

Two Sample t-test

data: mathematicians and accountants

t = 0.46359, df = 21, p-value = 0.6477

alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

-6.569496 10.338727

sample estimates:

mean of x mean of y

53.50000 51.61538 Comments on output:

- Fifth line: R computes a 95 \% confidence interval for \mu_X - \mu_Y

(\mu_X - \mu_Y) \in [-6.569496, 10.338727]

- Interpretation: If you repeat the experiment (on new data) over and over, the interval [a,b] will contain \mu_X - \mu_Y about 95\% of the times

Two Sample t-test

data: mathematicians and accountants

t = 0.46359, df = 21, p-value = 0.6477

alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

-6.569496 10.338727

sample estimates:

mean of x mean of y

53.50000 51.61538 Comments on output:

- Seventh line: R computes sample mean for the two populations

- Sample mean for

mathematiciansis 53.5 - Sample mean for

accountantsis 51.61538

- Sample mean for

Two Sample t-test

data: mathematicians and accountants

t = 0.46359, df = 21, p-value = 0.6477

alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

-6.569496 10.338727

sample estimates:

mean of x mean of y

53.50000 51.61538 Conclusion: The p-value is p = 0.6477

- Since p > 0.05 we do not reject H_0

- Hence \mu_X and \mu_Y appear to be similar

- Average pay levels seem to be the same for both professions

Comment on Assumptions

The previous two-sample t-test was conducted under the following assumptions:

- Wages data is normally distributed

- The two populations have equal variance

Using R, we can plot the data to see if these are reasonable (graphical exploration)

Warnings: Even if the assumptions hold

- we cannot expect the samples to be exactly normal (bell-shaped)

- rather, look for approximate normality

- we cannot expect the sample variances to match

- rather, look for a similar spread in the data

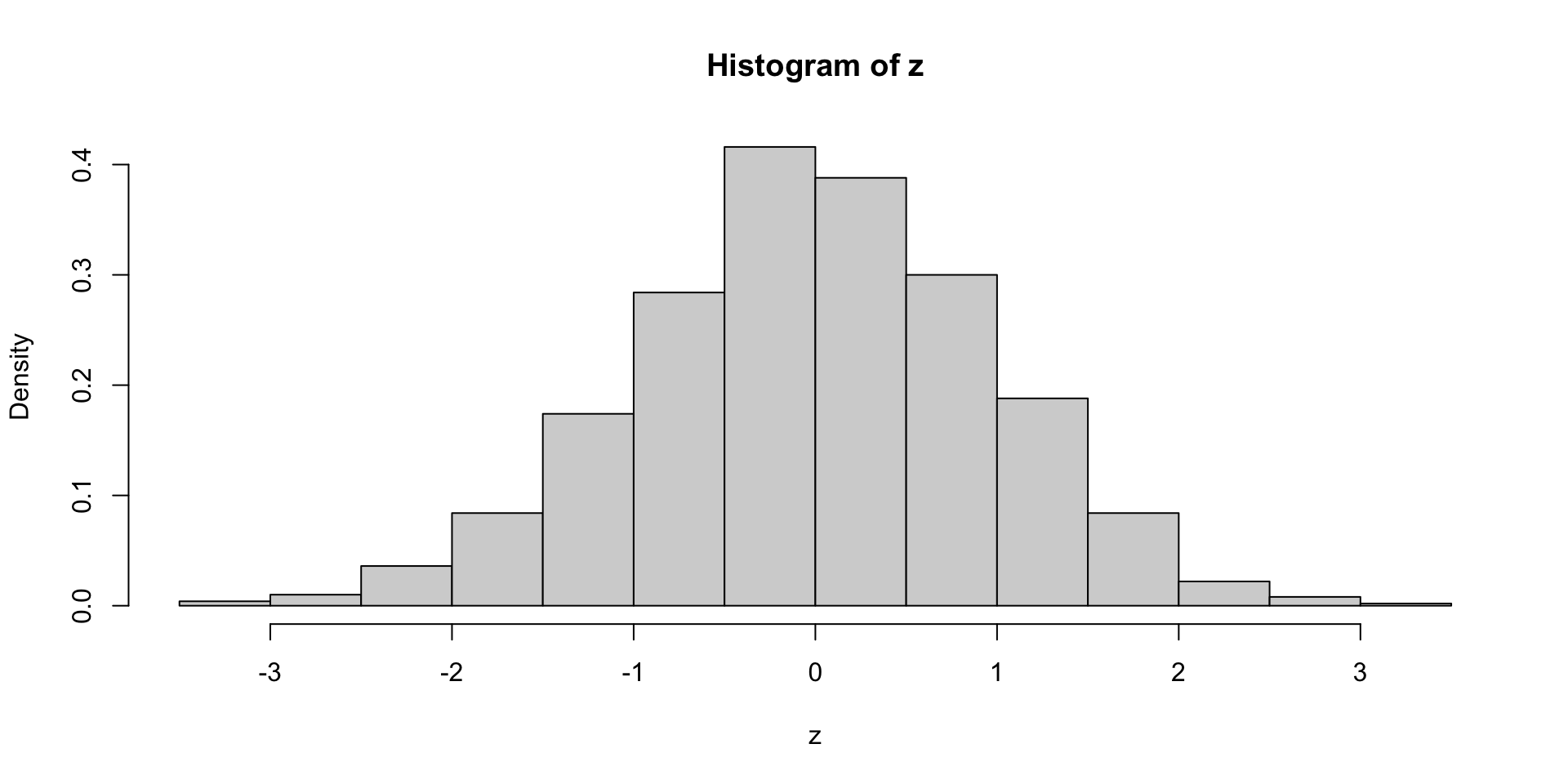

Estimating the sample distribution in R

Suppose given a data sample stored in a vector z

If the sample is large, we can check normality by plotting the histogram of

zExample:

zsample of size 1000 form N(0,1) – Its histogram resembles N(0,1)

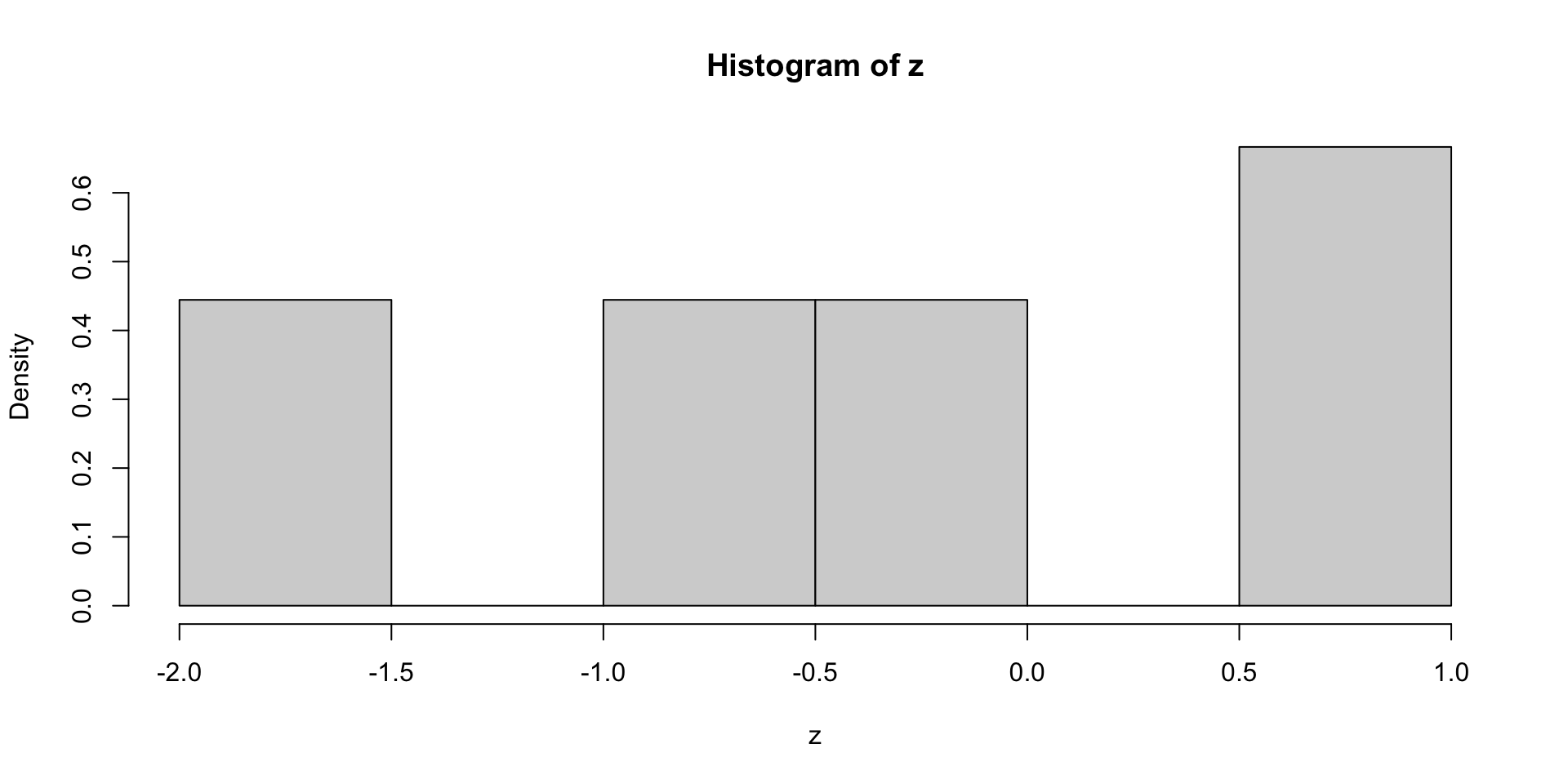

Drawback: Small samples \implies hard to check normality from histogram

- This is true even if the data is normal

- Example:

zbelow is sample of size 9 from N(0,1) – But histogram not normal

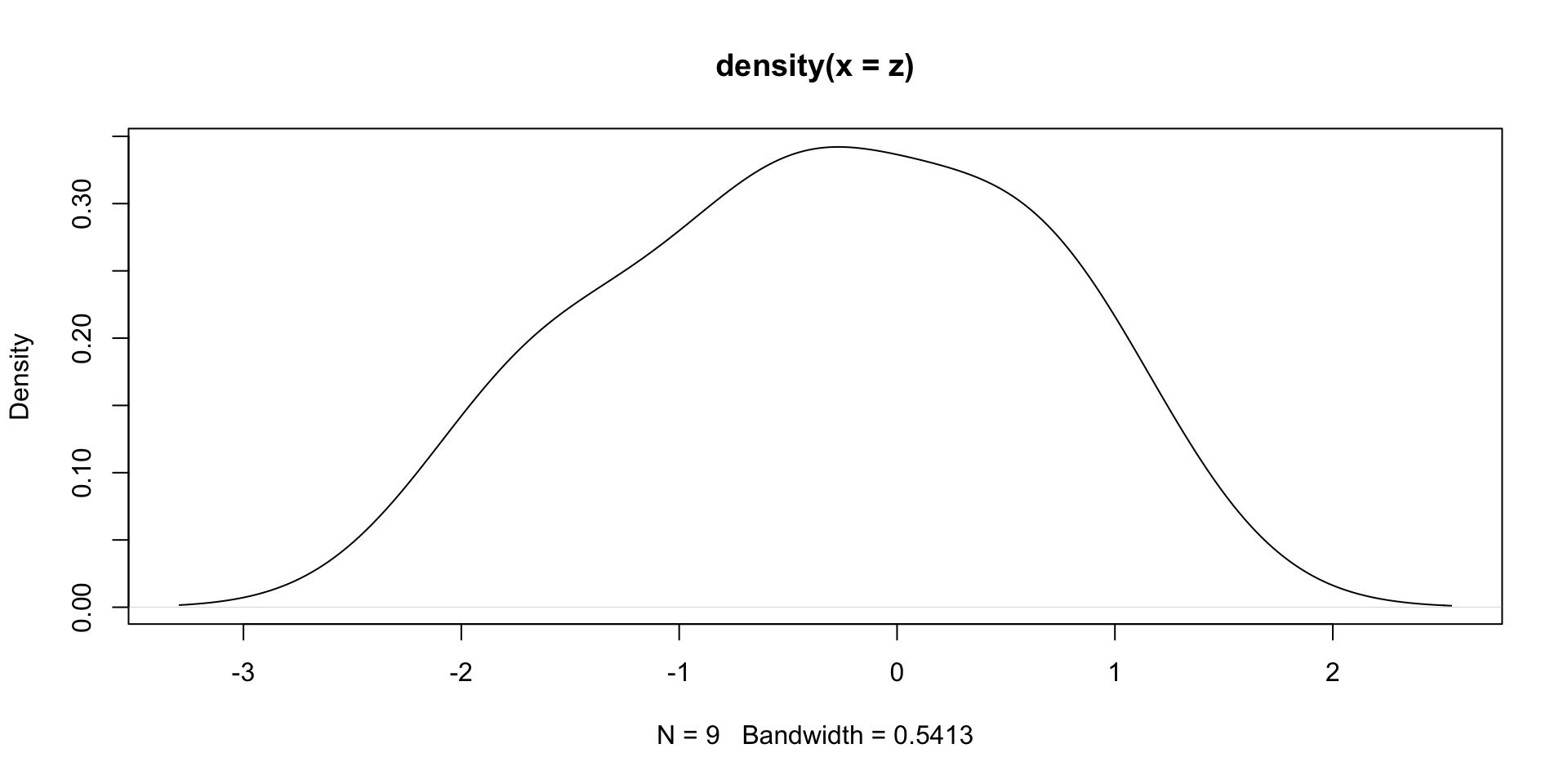

Solution: Suppose given iid sample z from a distribution f

The command

density(z)estimates the population distribution f

(Estimate based on the sampling distribution ofzand smoothing - Not easy task)Example:

zas in previous slide. The plot ofdensity(z)shows normal behavior

The R object density(z) models a 1D function (the estimated distribution of z)

- As such, it contains a grid of x values, with associated y values

- x values are stored in vector

density(z)$x - y values are stored in vector

density(z)$y

- x values are stored in vector

- These values are useful to set the axis range in a plot

dz <- density(z)

plot(dz, # Plot dz

xlim = range(dz$x), # Set x-axis range

ylim = range(dz$y)) # Set y-axis rangeAxes range set as the min and max values of components of dz

Checking the Assumptions on our Example

# Compute the estimated distributions

d.math <- density(mathematicians)

d.acc <- density(accountants)

# Plot the estimated distributions

plot(d.math, # Plot d.math

xlim = range(c(d.math$x, d.acc$x)), # Set x-axis range

ylim = range(c(d.math$y, d.acc$y)), # Set y-axis range

main = "Estimated Distributions of Wages") # Add title to plot

lines(d.acc, # Layer plot of d.acc

lty = 2) # Use different line style

legend("topleft", # Add legend at top-left

legend = c("Mathematicians", # Labels for legend

"Accountants"),

lty = c(1, 2)) # Assign curves to legendAxes range set as the min and max values of components of d.math and d.acc

Wages data looks approximately normally distributed (roughly bell-shaped)

The two populations have similar variance (spreads look similar)

Conclusion: Two-sample t-test with equal variance is appropriate \implies accept H_0

Part 4:

The Welch t-test

Samples with different variance

We just examined the two-sample t-tests

This assumes independent normal populations with equal variance

\sigma_X^2 = \sigma_Y^2

Question: What happens if variances are different?

Answer: Use the Welch Two-sample t-test

- This is a generalization of the two-sample t-test to the case \sigma_X^2 \neq \sigma_Y^2

- In R it is performed with

t.test(x, y) - Note that we are just omitting the option

var.equal = TRUE - Equivalently, you may specify

var.equal = FALSE

The Welch two-sample t-test

Welch t-test consists in computing the Welch statistic w = \frac{\overline{x} - \overline{y}}{ \sqrt{ \dfrac{s_X^2}{n} + \dfrac{s_Y^2}{m} } }

If sample sizes m,n > 5, then w is approximately t-distributed

- Degrees of freedom are not integer, and depend on S_X, S_Y, n, m

If variances are similar, the welch statistic is comparable to the t-statistic

w \approx t : = \frac{ \overline{x} - \overline{y} }{s_p \sqrt{ \dfrac{1}{n} + \dfrac{1}{m} }}

Welch t-test Vs two-sample t-test

If variances are similar:

- Welch statistic and t-statistic are similar

- p-value from Welch t-test is similar to p-value from two-sample t-test

- Since p-values are similar, most times the 2 tests yield same decision

- The tests can be used interchangeably

If variances are very different:

- Welch statistic and t-statistic are different

- p-values from the two tests can differ a lot

- The two tests might give different decision

- Wrong to apply two-sample t-test, as variances are different

The Welch two-sample t-test in R

# Enter Wages data

mathematicians <- c(36, 40, 46, 54, 57, 58, 59, 60, 62, 63)

accountants <- c(37, 37, 42, 44, 46, 48, 54, 56, 59, 60, 60, 64, 64)

# Perform Welch two-sample t-test with null hypothesis mu_X = mu_Y

# Store result of t.test in answer

answer <- t.test(mathematicians, accountants)

# Print answer

print(answer)- Note:

- This is almost the same code as in Slide 86

- Only difference: we are omitting the option

var.equal = TRUEint.test

Welch Two Sample t-test

data: mathematicians and accountants

t = 0.46546, df = 19.795, p-value = 0.6467

alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

-6.566879 10.336109

sample estimates:

mean of x mean of y

53.50000 51.61538 Comments on output:

- First line: R tells us that a Welch Two-Sample t-test is performed

- The rest of the output is similar to classic t-test

- Main difference is that p-value and t-statistic differ from classic t-test

Welch Two Sample t-test

data: mathematicians and accountants

t = 0.46546, df = 19.795, p-value = 0.6467

alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

-6.566879 10.336109

sample estimates:

mean of x mean of y

53.50000 51.61538 Comments on output:

- Third line:

- The Welch t-statistic is w = 0.46546 (standard t-test gave t = 0.46359)

- Degrees of freedom are fractionary \rm{df} = 19.795 (standard t-test \rm{df} = 21)

- The Welch t-statistic is approximately t-distributed with W \approx t_{19.795}

- Fifth line: The confidence interval for \mu_X - \mu_Y is also different

Welch Two Sample t-test

data: mathematicians and accountants

t = 0.46546, df = 19.795, p-value = 0.6467

alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

-6.566879 10.336109

sample estimates:

mean of x mean of y

53.50000 51.61538 Conclusion: The p-values obtained with the 2 tests are almost the same

Welch t-test: p-value = 0.6467 \qquad Classic t-test: p-value = 0.6477

Both test: p > 0.05, and therefore do not reject H_0

Note: This was expected

- The spread of the two populations is similar \implies \, \sigma_X^2 \approx \sigma_Y^2

- Hence, Welch t-statistic approximates t-statistic \implies p-values are similar

Exercise

We compare the Effect of Two Treatments on Blood Pressure Change

Both treatments are given to a group of patients

Measurements of changes in blood pressure are taken after 4 weeks of treatment

Note that changes represent both positive and negative shifts in blood pressure

| Treat. A | -1.9 | -2.5 | -2.1 | -2.4 | -2.6 | -1.9 | ||||||

| Treat. B | -1.1 | -0.9 | -1.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.6 | -5 | -2.4 | -1.5 | 2.3 | -2.8 | 2.1 |

# Enter changes in Blood pressure data

trA <- c(-1.9, -2.5, -2.1, -2.4, -2.6, -1.9)

trB <- c(-1.1, -0.9, -1.4, 0.2, 0.3, 0.6, -5,

-2.4, -1.5, 2.3, -2.8, 2.1)

cat("Mean of Treatment A:", mean(trA), "Mean of Treatment B:", mean(trB))Mean of Treatment A: -2.233333 Mean of Treatment B: -0.8Sample means show both Treatments are effective in decreasing blood pressure

However Treatment A seems slightly better

Question: Perform a t-test to see if Treatment A is better H_0 \colon \mu_A = \mu_B \, , \qquad H_1 \colon \mu_A < \mu_B

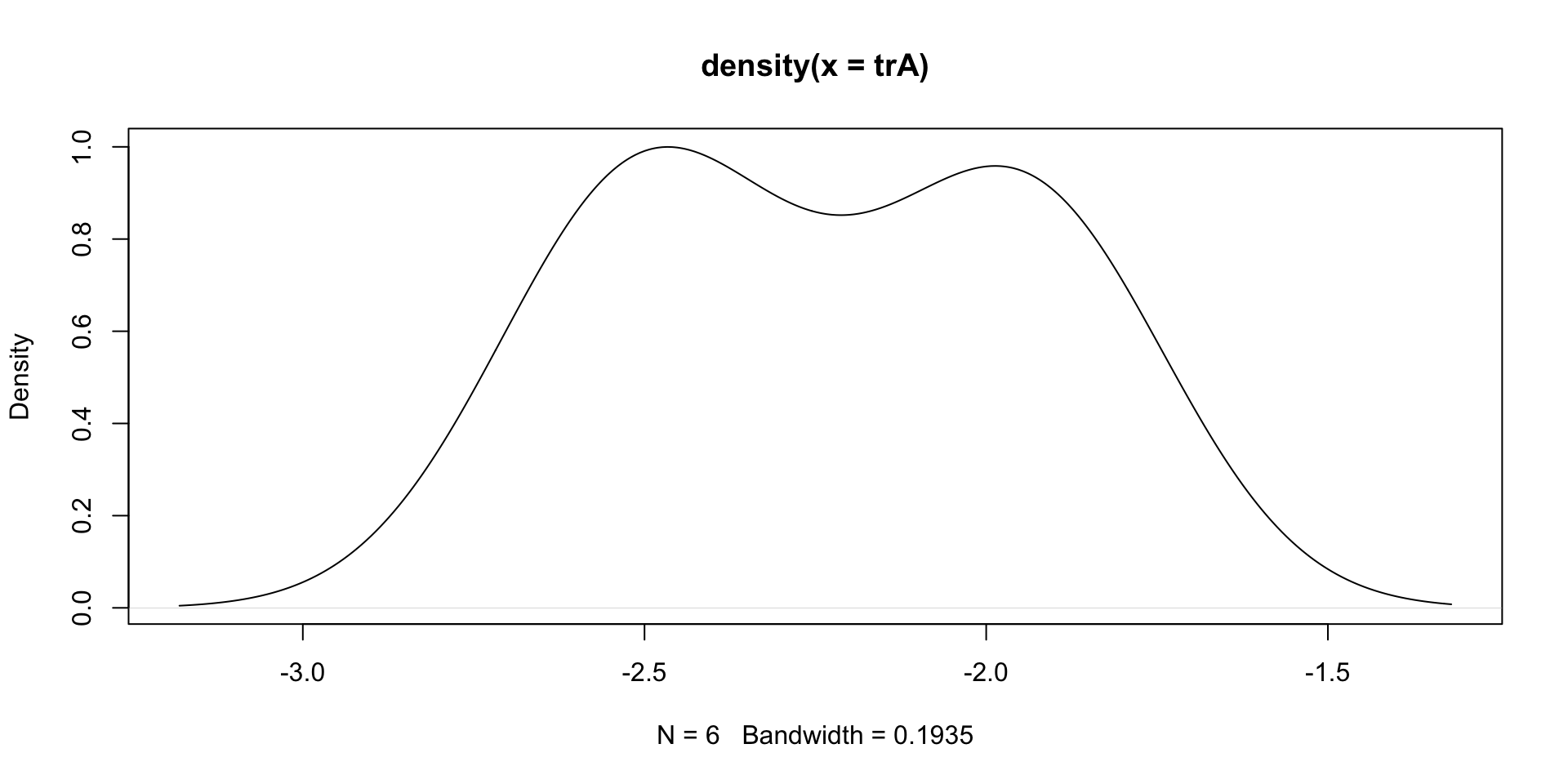

Solution: Estimated density of Treatment A

- Estimated density looks bell-shaped \implies First population is normal

- Sample seems concentrated between -3 and -1.5

Estimated density of Treatment B

- Estimated density looks bell-shaped \implies Second population is normal

- Sample seems concentrated between -7 and 4

Findings

- Both populations are normal \implies t-test is appropriate

- First sample seems concentrated between -3 and -1.5

- Second sample seems concentrated between -7 and 4

- Treatment B has larger spread

- Therefore we suspect that populations have different variance

\sigma_A^2 \neq \sigma_B^2

Conclusion:

- The Welch t-test is appropriate

- Two sample t-test would not be appropriate (as it assumes equal variance)

Apply the Welch t-test

We are testing the one-sided hypothesis

H_0 \colon \mu_A = \mu_B \, , \qquad H_1 \colon \mu_A < \mu_B

# Perform Welch t-test and retrieve p-value

ans <- t.test(trA, trB, alt = "less", var.equal = F)

ans$p.value[1] 0.01866013The p-value is p < 0.05

We reject H_0 \implies Treatment A is more effective

Two-sample t-test gives different decision

We are testing the one-sided hypothesis

H_0 \colon \mu_A = \mu_B \, , \qquad H_1 \colon \mu_A < \mu_B

# Perform two-sample t-test and retrieve p-value

ans <- t.test(trA, trB, alt = "less", var.equal = T)

ans$p.value[1] 0.05836482The p-value is p > 0.05

H_0 cannot be rejected \implies There is no evidence that Treatment A is better

Wrong conclusion, because two-sample t-test does not apply

Disclaimer

The previous data was synthetic, and the background story was made up!

Nonetheless, the example is still valid

To construct the data, I sampled as follows

- Treatment A: Sample of size 6 from N(-2,1)

- Treatment B: Sample of size 12 from N(-1.5,9)

We see that \mu_A < \mu_B \,, \qquad \sigma_A^2 \neq \sigma_B^2

This tells us that:

- We can expect that some samples will support that \mu_A < \mu_B

- Two-sample t-test is inappropriate because \sigma_A^2 \neq \sigma_B^2

Generating the Data

Click here to see the code I used

# Set seed for random generation

# This way you always get the same random numbers when

# you run this code

set.seed(21)

repeat {

# Generate random samples

x <- rnorm(6, mean = -2, sd = 1)

y <- rnorm(12, mean = -1.5, sd = 3)

# Round x and y to 1 decimal point

x <- round(x, 1)

y <- round(y, 1)

# Perform one-sided t-tests for alternative hypothesis mu_x < mu_y

ans_welch <- t.test(x, y, alt = "less", var.equal = F)

ans_t_test <- t.test(x, y, alt = "less", var.equal = T)

# Check that Welch test succeeds and two-sample test fails

if (ans_welch$p.value < 0.05 && ans_t_test$p.value > 0.05) {

cat("Data successfully generated!!!\n\n")

cat("Synthetic Data TrA:", x, "\n")

cat("Synthetic Data TrB:", y, "\n\n")

cat("Welch t-test p-value:", ans_welch$p.value, "\n")

cat("Two-sample t-test p-value:", ans_t_test$p.value)

break

}

}Data successfully generated!!!

Synthetic Data TrA: -1.9 -2.5 -2.1 -2.4 -2.6 -1.9

Synthetic Data TrB: -1.1 -0.9 -1.4 0.2 0.3 0.6 -5 -2.4 -1.5 2.3 -2.8 2.1

Welch t-test p-value: 0.01866013

Two-sample t-test p-value: 0.05836482Method:

Sample the data as in previous slide (round to 1 d.p. for cleaner looking data)

Repeat until Welch test succeeds, and two-sample t-test fails \text{p-value of Welch test } \, < 0.05 < \, \text{p-value of Two-sample t-test}

Part 5:

The t-test for

paired samples

Paired samples

Assume to have two sample with same size

Sometimes the two samples depend on each other in some way

- Twin studies:

- Twins are used as pairs (to control genetic or environmental factors)

- Example: test effectiveness of a medical treatment against placebo

- The two samples are clearly dependent

(think of twins as the same person)

- As such, the usual two-sample t-test is not applicable

(because it assumes independence)

Paired samples

Assume to have two sample with same size

Sometimes the two samples depend on each other in some way

- Pre-test and Post-test

- Measure the outcome of a certain action

- Example: does this module work for teaching R?

- We can assess the effectiveness of something with a pre-test and a post-test

- The two samples are clearly dependent

(each individual takes a test twice) - As such, the usual two-sample t-test is not applicable

(because it assumes independence)

The paired t-test

Suppose given two samples

Sample x_1, \ldots, x_n from N(\mu_X,\sigma^2_X)

Sample y_1, \ldots, y_n from N(\mu_Y,\sigma^2_Y)

The hypotheses for difference in means are H_0 \colon \mu_X = \mu_Y \,, \quad \qquad H_1 \colon \mu_X \neq \mu_Y \,, \quad \mu_X < \mu_Y \,, \quad \text{ or } \quad \mu_X > \mu_Y

The paired t-test

Assumption: The data is paired, meaning that the differences

d_i = x_i - y_i \,\, \text{ are iid} \,\, N(\mu,\sigma^2) \quad \text{where} \quad \mu := \mu_X - \mu_Y

The hypotheses for the difference in means are equivalent to

H_0 \colon \mu = 0 \,, \quad \qquad H_1 \colon \mu \neq 0 \,, \quad \mu < 0 \,, \quad \text{ or } \quad \mu > 0

These can be tested with a one-sample t-test

R commands: The paired t-test can be called with the equivalent commands

t.test(x, y, paired = TRUE)\qquad \quad H_0 \colon \mu_X = \mu_Yt.test(x - y)\qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad\qquad H_0 \colon \mu = 0

Example 1: The 2008 crisis (again!)

| Month | J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCI 2007 | 86 | 86 | 88 | 90 | 99 | 97 | 97 | 96 | 99 | 97 | 90 | 90 |

| CCI 2009 | 24 | 22 | 21 | 21 | 19 | 18 | 17 | 18 | 21 | 23 | 22 | 21 |

Data: Monthly Consumer Confidence Index (CCI) in 2007 and 2009

Question: Did the crash of 2008 have lasting impact upon CCI?

Observations:

- Data shows a massive drop in CCI between 2007 and 2009

- Data is clearly paired (Pre-test and Post-test situation)

Method: Use paired t-test to investigate drop in mean CCI

H_0 \colon \mu_{2007} = \mu_{2009} \,, \quad H_1 \colon \mu_{2007} > \mu_{2009}

Perform paired t-test

# Enter CCI data

score_2007 <- c(86, 86, 88, 90, 99, 97, 97, 96, 99, 97, 90, 90)

score_2009 <- c(24, 22, 21, 21, 19, 18, 17, 18, 21, 23, 22, 21)

# Perform paired t-test and print p-value

ans <- t.test(score_2007, score_2009, paired = T, alt = "greater")

ans$p.value[1] 2.430343e-13The p-value is significant: \,\, p < 0.05 \, \implies \, reject H_0 \, \implies \, Drop in CCI

Warning

It would be wrong to use a two-sample t-test

This is because the samples are paired, and hence dependent

This is further supported by computing the correlation

High correlation implies dependence

[1] -0.6076749Example 2: Water quality samples

Researchers wish to measure water quality

There are two possible tests, one less expensive than the other

10 water samples were taken, and each was measured both ways

| method1 | 45.9 | 57.6 | 54.9 | 38.7 | 35.7 | 39.2 | 45.9 | 43.2 | 45.4 | 54.8 |

| method2 | 48.2 | 64.2 | 56.8 | 47.2 | 43.7 | 45.7 | 53.0 | 52.0 | 45.1 | 57.5 |

Question: Do the tests give the same results?

Observation: The data is paired (twin study situation)

Method: Use paired t-test to investigate equality of results

H_0 \colon \mu_1 = \mu_2 \,, \quad H_1 \colon \mu_1 \neq \mu_2

Perform paired t-test

# Enter tests data

method1 <- c(45.9, 57.6, 54.9, 38.7, 35.7, 39.2, 45.9, 43.2, 45.4, 54.8)

method2 <- c(48.2, 64.2, 56.8, 47.2, 43.7, 45.7, 53.0, 52.0, 45.1, 57.5)

# Perform paired t-test and print p-value

ans <- t.test(method1, method2, paired = T)

ans$p.value[1] 0.0006648526p-value is significant: \,\, p < 0.05 \implies reject H_0 \implies Methods perform differently

Warning

It would be wrong to use a two-sample t-test

This is because the samples are paired, and hence dependent

This is also supported by high samples correlation

[1] 0.9015147Warning

In this Example, performing a two-sample t-test would lead to wrong decision

# Perform Welch t-test and print p-value

ans <- t.test(method1, method2, paired = F) # paired = F is default

ans$p.val[1] 0.1165538Wrong conclusion: \,\, p > 0.05 \implies can’t reject H_0 \implies Methods perform similarly

Bottom line: The data is paired, therefore a paired t-test must be used

Part 6:

More on Vectors

More on vectors

- We have seen vectors of numbers

- Further type of vectors are:

- Character vectors

- Logical vectors

Character vectors

- A character vector is a vector of text strings

- Elements are specified and printed in quotes

- You can use single- or double-quote symbols to specify strings

- This is as long as the left quote is the same as the right quote

Character vectors

Print and cat produce different output on character vectors:

print(x)prints all the strings inxseparatelycat(x)concatenates strings. There is no way to tell how many were there

Logical vectors

- Logical vectors can take the values

TRUE,FALSEorNA TRUEandFALSEcan be abbreviated withTandFNAstands for not available

Logical vectors

Logical vectors are extremely useful to evaluate conditions

Example:

- given a numerical vector

x - we want to count how many entries are above a value

t

- given a numerical vector

# Generate a vector containing sequence 1 to 8

x <- seq(from = 1 , to = 8, by = 1)

# Generate vector of flags for entries strictly above 5

y <- ( x > 5 )

cat("Vector x is: (", x, ")")

cat("Entries above 5 are: (", y, ")")Vector x is: ( 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 )Entries above 5 are: ( FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE TRUE )Logical vectors – Application

- Generate a vector of 1000 numbers from N(0,1)

- Count how many entries are above the mean 0

- Since there are many (1000) entries, we expect a result close to 500

- This is because sample mean converges to true mean 0

Question: How to do this?

Hint: T/F are interpreted as 1/0 in arithmetic operations

Logical vectors – Application

- The function

sum(x)sums the entries of a vectorx - We can use

sum(x)to count the number ofTentries in a logical vectorx

x <- rnorm(1000) # Generates vector with 1000 normal entries

y <- (x > 0) # Generates logical vector of entries above 0

above_zero <- sum(y) # Counts entries above zero

cat("Number of entries which are above the average 0 is", above_zero)

cat("This is pretty close to 500!")Number of entries which are above the average 0 is 527This is pretty close to 500!Missing values

- In practical data analysis, a data point is frequently unavailable

- Statistical software needs ways to deal with this

- R allows vectors to contain a special

NAvalue - Not Available NAis carried through in computations: operations onNAyieldNAas the result

Indexing vectors

Components of a vector can be retrieved by indexing

vector[k]returns k-th component ofvector

Replacing vector elements

To modify an element of a vector use the following:

vector[k] <- valuestoresvaluein k-th component ofvector

Vector slicing

Returning multiple items of a vactor is known as slicing

vector[c(k1, ..., kn)]returns componentsk1, ..., knvector[k1:k2]returns componentsk1tok2

Vector slicing

Deleting vector elements

- Elements of a vector

xcan be deleted by usingx[ -c(k1, ..., kn) ]which deletes entriesk1, ..., kn

# Create a vector x

x <- c(11, 22, 33, 44, 55, 66, 77, 88, 99, 100)

# Print vector x

cat("Vector x is:", x)

# Delete 2nd, 3rd and 7th entries of x

x <- x[ -c(2, 3, 7) ]

# Print x again

cat("Vector x with 2nd, 3rd and 7th entries removed:", x)Vector x is: 11 22 33 44 55 66 77 88 99 100Vector x with 2nd, 3rd and 7th entries removed: 11 44 55 66 88 99 100Logical Subsetting

- You can index or slice vectors by entering explicit indices

- You can also index vectors, or subset, by using logical flag vectors:

- Element is extracted if corresponding entry in the flag vector is TRUE

- Logical flag vectors should be the same length as vector to subset

Code: Suppose given a vector x

Create a flag vector by using

flag <- condition(x)

condition()is any function which returnsT/Fvector of same length asxSubset

xby usingx[flag]

Logical Subsetting

Example

- The following code extracts negative components from a numeric vector

- This can be done by using

x[ x < 0 ]

# Create numeric vector x

x <- c(5, -2.3, 4, 4, 4, 6, 8, 10, 40221, -8)

# Get negative components from x and store them in neg_x

neg_x <- x[ x < 0 ]

cat("Vector x is:", x)

cat("Negative components of x are:", neg_x)Vector x is: 5 -2.3 4 4 4 6 8 10 40221 -8Negative components of x are: -2.3 -8Logical Subsetting

Example

- The following code extracts components falling between

aandb - This can be done by using logical operator and

&x[ (x > a) & (x < b) ]

# Create numeric vector

x <- c(5, -2.3, 4, 4, 4, 6, 8, 10, 40221, -8)

# Get components between 0 and 100

range_x <- x[ (x > 0) & (x < 100) ]

cat("Vector x is:", x)

cat("Components of x between 0 and 100 are:", range_x)Vector x is: 5 -2.3 4 4 4 6 8 10 40221 -8Components of x between 0 and 100 are: 5 4 4 4 6 8 10The function Which

which()allows to convert a logical vectorflaginto a numeric index vectorwhich(flag)is vector of indices offlagwhich correspond toTRUE

# Create a logical flag vector

flag <- c(T, F, F, T, F)

# Indices for flag which

true_flag <- which(flag)

cat("Flag vector is:", flag)

cat("Positions for which Flag is TRUE are:", true_flag)Flag vector is: TRUE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSEPositions for which Flag is TRUE are: 1 4The function Which – Application

which() can be used to delete certain entries from a vector x

Create a flag vector by using

flag <- condition(x)

condition()is any function which returnsT/Fvector of same length asxDelete entries flagged by

conditionusing the codex[ -which(flag) ]

The function Which – Application

Example

# Create numeric vector x

x <- c(5, -2.3, 4, 4, 4, 6, 8, 10, 40221, -8)

# Print x

cat("Vector x is:", x)

# Flag positive components of x

flag_pos_x <- (x > 0)

# Remove positive components from x

x <- x[ -which(flag_pos_x) ]

# Print x again

cat("Vector x with positive components removed:", x)Vector x is: 5 -2.3 4 4 4 6 8 10 40221 -8Vector x with positive components removed: -2.3 -8Functions that create vectors

The main functions to generate vectors are

c()concatenateseq()sequencerep()replicate

We have already met c() and seq() but there are more details to discuss

Concatenate

Recall: c() generates a vector containing the input values

Concatenate

c()can also concatenate vectors- This was you can add entries to an existing vector

Concatenate

You can assign names to vector elements

This modifies the way the vector is printed

Concatenate

Given a named vector x

- Names can be extracted with

names(x) - Values can be extracted with

unname(x)

# Create named vector

x <- c(first = "Red", second = "Green", third = "Blue")

# Access names of x via names(x)

names_x <- names(x)

# Access values of x via unname(x)

values_x <- unname(x)

cat("Names of x are:", names(x))

cat("Values of x are:", unname(x))Names of x are: first second thirdValues of x are: Red Green BlueConcatenate

- All elements of a vector have the same type

- Concatenating vectors of different types leads to conversion

Sequence

- Recall the syntax of

seqisseq(from =, to =, by =, length.out =)

- Omitting the third argument assumes that

by = 1

Sequence

seq(x1, x2)is equivalent tox1:x2- Syntax

x1:x2is preferred toseq(x1, x2)

# Generate two vectors of integers from 1 to 6

x <- seq(1, 6)

y <- 1:6

cat("Vector x is:", x)

cat("Vector y is:", y)

cat("They are the same!")Vector x is: 1 2 3 4 5 6Vector y is: 1 2 3 4 5 6They are the same!Replicate

rep generates repeated values from a vector:

xvectornintegerrep(x, n)repeatsntimes the vectorx

# Create a vector with 3 components

x <- c(2, 1, 3)

# Repeats 4 times the vector x

y <- rep(x, 4)

cat("Original vector is:", x)

cat("Original vector repeated 4 times:", y)Original vector is: 2 1 3Original vector repeated 4 times: 2 1 3 2 1 3 2 1 3 2 1 3Replicate

The second argument of rep() can also be a vector:

- Given

xandyvectors rep(x, y)repeats entries ofxas many times as corresponding entries ofy

x <- c(2, 1, 3) # Vector to replicate

y <- c(1, 2, 3) # Vector saying how to replicate

z <- rep(x, y) # 1st entry of x is replicated 1 time

# 2nd entry of x is replicated 2 times

# 3rd entry of x is replicated 3 times

cat("Original vector is:", x)

cat("Original vector repeated is:", z)Original vector is: 2 1 3Original vector repeated is: 2 1 1 3 3 3Replicate

rep()can be useful to create vectors of labels- Example: Suppose we want to collect some numeric data on 3 Cats and 4 Dogs

Comments on command

t.test(x, y)mu = mu0tells R to test null hypothesis: H_0 \colon \mu_X - \mu_Y = \mu_0 \qquad \quad (\text{default is } \, \mu_0 = 0)var.equal = Ttells R to assume that populations have same variance \sigma_X^2 = \sigma^2_YIn this case R computes the t-statistic with formula discussed earlier t = \frac{ \overline{x} - \overline{y} }{s_p \sqrt{ \dfrac{1}{n} + \dfrac{1}{m} }}