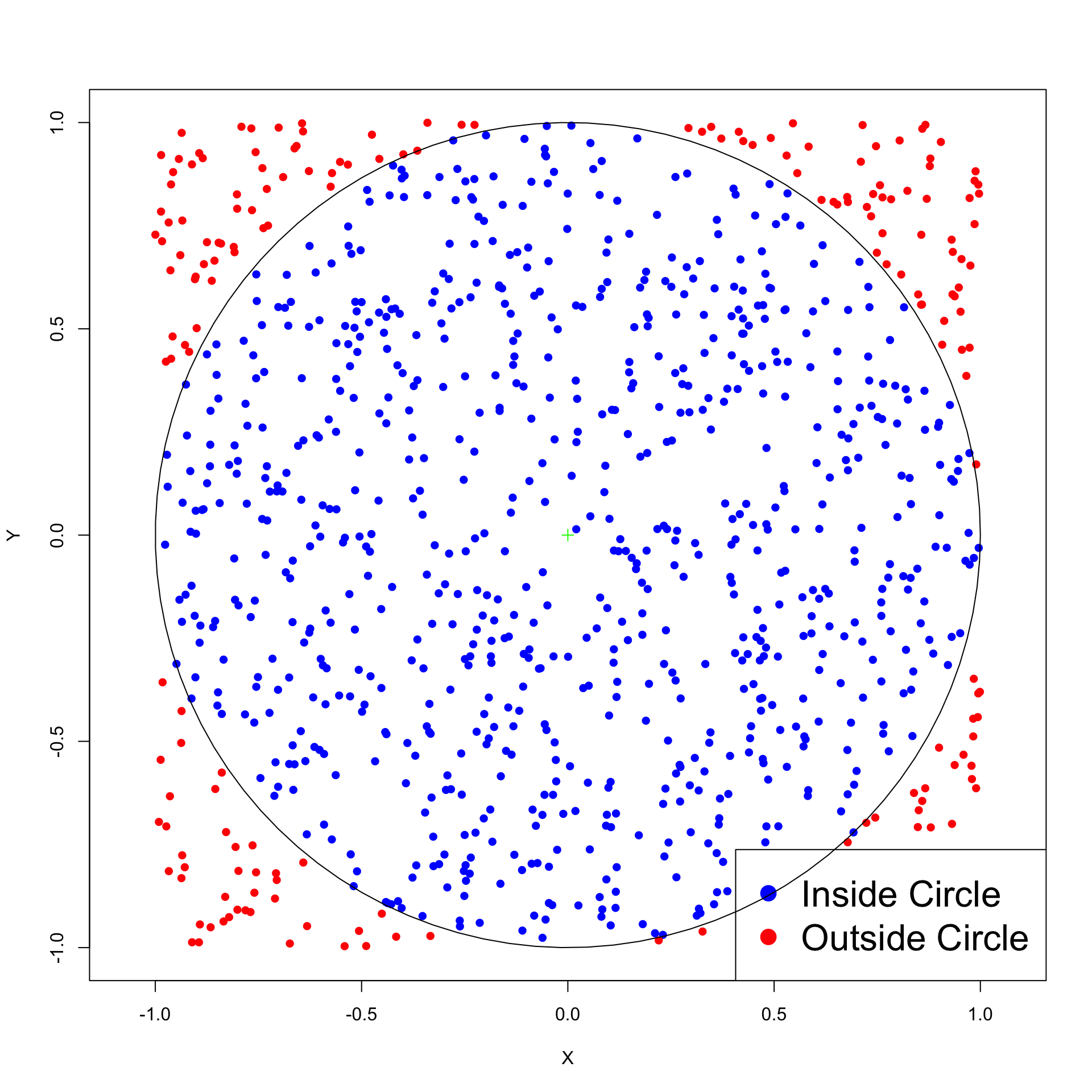

After 10000 iterations pi is 3.14440000, error is 0.00280735

After 20000 iterations pi is 3.12820000, error is 0.01339265

After 30000 iterations pi is 3.13280000, error is 0.00879265

After 40000 iterations pi is 3.14110000, error is 0.00049265

After 50000 iterations pi is 3.13248000, error is 0.00911265

After 60000 iterations pi is 3.13473333, error is 0.00685932

After 70000 iterations pi is 3.13411429, error is 0.00747837

After 80000 iterations pi is 3.13495000, error is 0.00664265

After 90000 iterations pi is 3.13333333, error is 0.00825932

After 100000 iterations pi is 3.13200000, error is 0.00959265Main Bootstrap idea

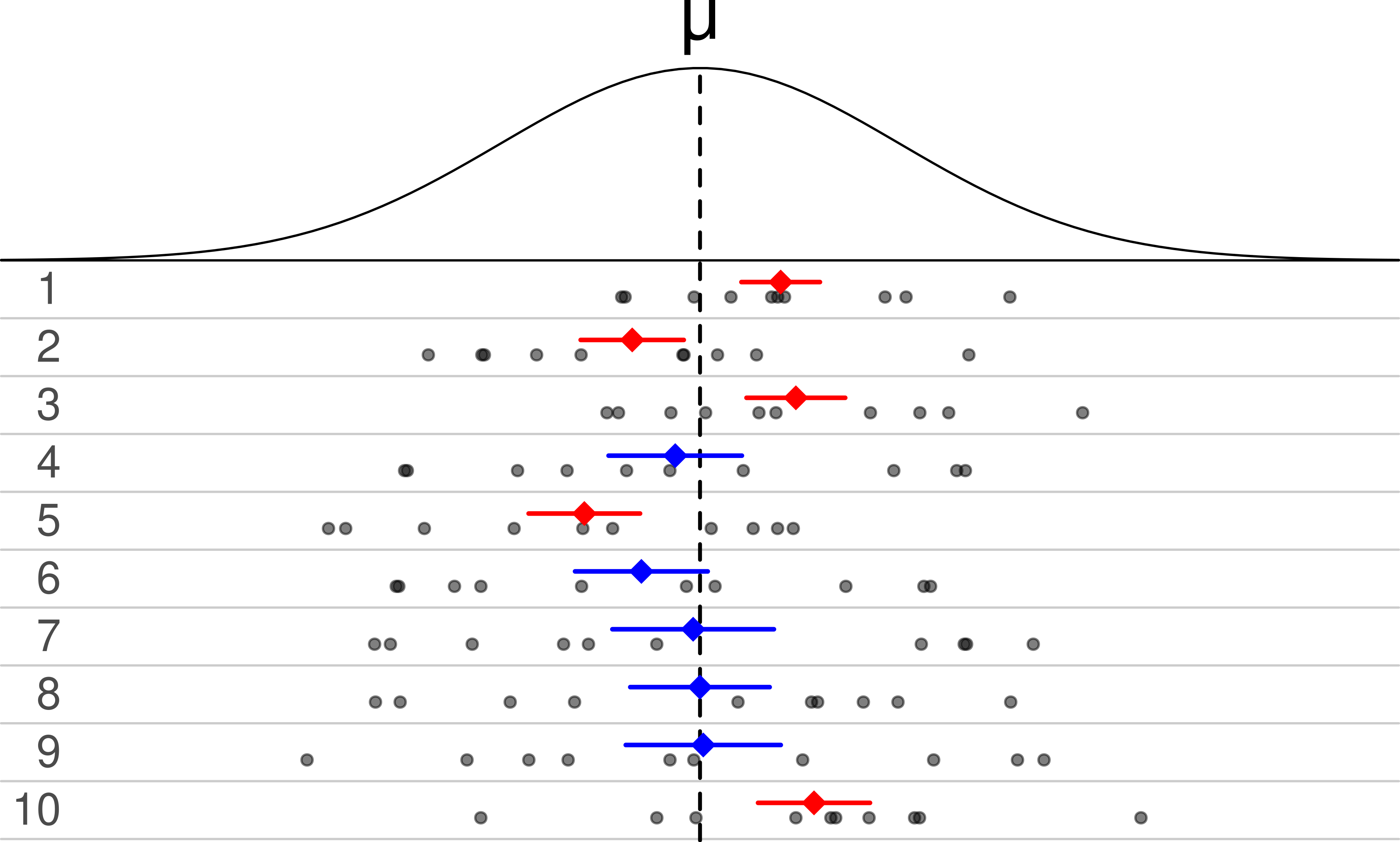

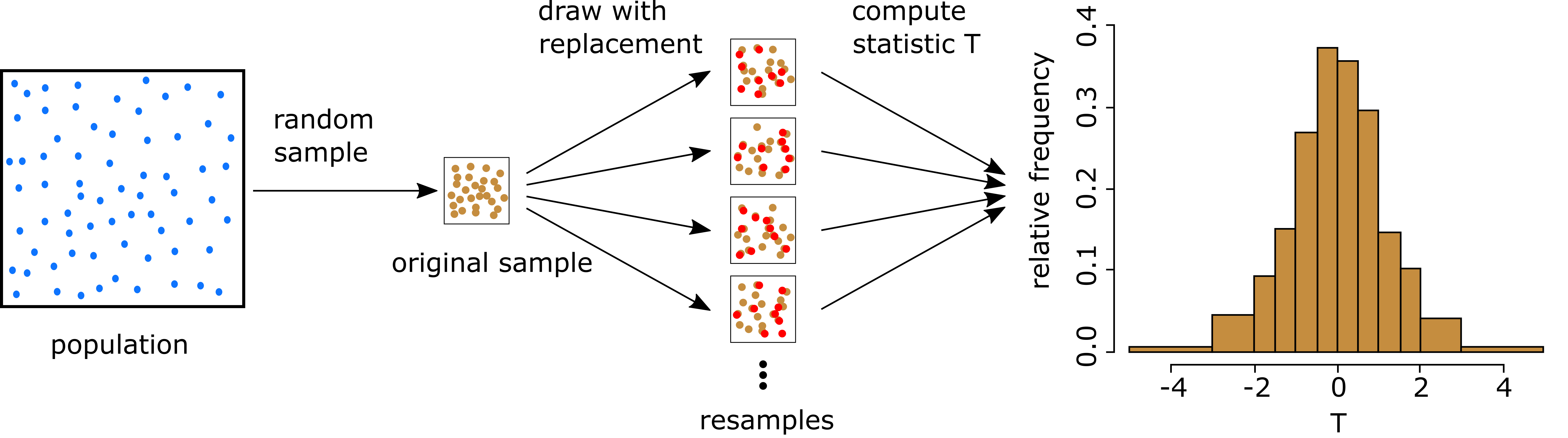

Setting: Assume given the original sample x_1,\ldots,x_n from unknown population f

Bootstrap: Regard the sample as the whole population

Replace the unknown distribution f with the sample distribution \hat{f}(x) = \begin{cases} \frac1n & \quad \text{ if } \, x \in \{x_1, \ldots, x_n\} \\ 0 & \quad \text{ otherwise } \end{cases}

Any sampling will be done from \hat{f} \qquad \quad (motivated by Glivenko-Cantelli Thm)

Note: \hat{f} puts mass \frac1n at each sample point

Drawing an observation from \hat f is equivalent to drawing one point at random from the original sample \{x_1,\ldots,x_n\}